SAN SEBASTIÁN 2025 Competición

Agnieszka Holland • Directora de Franz

"Si quisiese encontrar una nueva perspectiva, debería buscar fragmentos, piezas, puzzles y capas; tuve que hacer algo divertido"

por Olivia Popp

- La cineasta polaca explora su conexión personal con su protagonista, y cómo quiso devolverlo a la vida de una forma luminosa y original

Este artículo está disponible en inglés.

After a run in Toronto’s Special Presentations strand for its world premiere and being selected as Poland’s Oscars entry (see the news), Franz [+lee también:

crítica

tráiler

entrevista: Agnieszka Holland

ficha de la película] by renowned Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland now comes to the 73rd San Sebastián International Film Festival, vying for the Golden Shell in the main competition. At a round-table during the Basque festival, Holland explored the origins of the stylistic approach to this non-linear, semi-experimental pseudo-biopic of literary icon Franz Kafka, her own connections to the author and using the creative freedoms she has in an increasingly oppressive world.

Holland explained that the seeds for Franz were planted around four years ago while creating Charlatan [+lee también:

crítica

tráiler

entrevista: Agnieszka Holland

ficha de la película] (2021), both of which were written by Marek Epstein. “It was a very good collaboration, and I thought it was a really great basis on which to make something together. I was thinking about Franz Kafka as someone who was like my companion since I was a teenager. I knew that I could not do it as a regular, classic biopic, because it’s not relevant.” The film began in a more classical biopic format, as written by Epstein, but Holland pushed for the tale to be much more experimental.

“If I wanted to somehow find a new perspective myself, I had to look for fragments, pieces, puzzles and layers – I had to make it funky. I had to break that visual stereotype about Kafka that he is always in shadow, in black and white, and is a tortured, crooked figure. It’s not true. Let’s give him a chance to see the light.” She also felt frustrated about conventional biopics relying so heavily on exposition. “Most of the storytelling energy is going into staging the information in which you then make up some kind of drama, but I hate it. This is boring to me, and I did not want to do it.”

Holland has actively sought to create very distinct projects, inventing something completely different after her acclaimed Green Border [+lee también:

crítica

tráiler

ficha de la película], which tackled the refugee crisis on the Belarus-Polish border. “I want to maintain my curiosity about cinema and about life, even if my vision of the world is very dark. I don’t think we are going in the right direction as humanity. I think that, unfortunately, Kafka as a prophet will become relevant again. The only asset I have now is my freedom.”

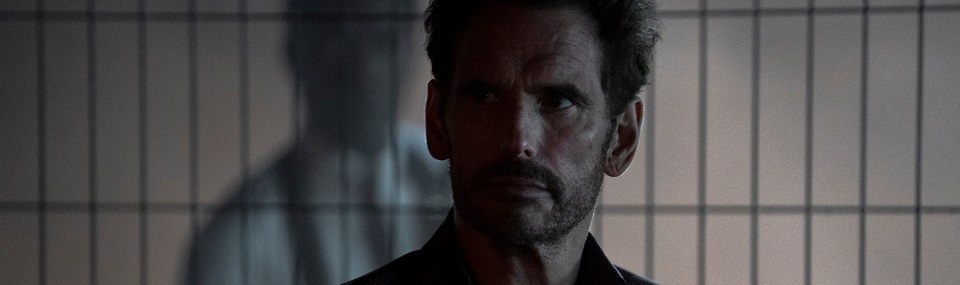

Her Franz is brought to life by young German actor Idan Weiss, who embodies the writer with such spunk and fervour – but without so much direct guidance from Holland, she explained. “I did not have a lot of conversations with Idan, actually, because he was so excited and afraid of what was going on, as he didn’t have a lot of big movie experience. He’s a young man and is pretty private, and I didn’t want to overwhelm him with a lot of notes and literature. He was preparing by himself and in a strange way, because he locked himself in his flat for two months. But I immediately had the feeling, when I met him and saw him on video, that he is Franz to a T – not only in how he looks, but also in his strange and extremely honest sensibility.”

Instead, Holland took a perhaps fittingly unconventional approach to exploring the character with Weiss. “The first thing I asked him to do was to watch videos where Rafael Nadal is playing tennis. He used to have special tics before every ball he was hitting, like [touching and tapping on his body]. Kafka was certainly neuro-atypical to some extent. It gives some kind of special connection to other people, like a lot of today’s young people. He’s like a swimmer who is always moving because if not, he will drown. I think that Franz had different tactics so as not to drown and to overcome the horror of the world.”

She explained how several test screenings for younger audiences resonated, especially in its humour, whereas the grown-up audience did not laugh so much. “The [younger people] connected to him exactly as somebody who is similar to them, who has that difficulty in communicating through touch and in an analogue way – who feels that he doesn’t fit in or is strange.”

Holland herself also expressed an emotional closeness with Kafka and his work. “When I was [a few decades younger], I became obsessed with Franz. When reading his letters, I felt the kind of closeness which you only have with people you care about enormously. I felt like I had to protect him somehow. When I was analysing the character of his favourite sister, Ottla, I thought she certainly had that kind of relationship with him: admiration and, at the same time, a mix of fear and irritation that he would fall apart or do something to hurt himself.

“I wanted to be close to him like that. Somehow, it was a fantasy. What I think made him feel so close to me was that he had an identity where he was not at home in any place, with any language or in any nation, at that time. And I have felt very much like that until now, and I am still feeling like that. It was his weakness and his strength.”

¿Te ha gustado este artículo? Suscríbete a nuestra newsletter y recibe más artículos como este directamente en tu email.