If Tahrir were told After the Battle

- Egyptian filmmaker Yousry Nasrallah is back in Cannes with a fiction - the first real fiction since the beginning of the Arab Spring - about his country's revolution

After an appearance in Cannes last year out of the competition with the Egyptian ensemble film 18 Days, filmmaker Yousry Nasrallah is now back on the Croisette with a fiction - the first real fiction since the beginning of the Arab Spring - about his country's revolution. After the Battle (Baad El Mawkeaa), a Franco-Egyptian co-production, is running in the official competition at the 65th Cannes Film Festival.

Nasrallah didn't want to follow a screenplay to shoot his film, but he used a very famous scene in world news as its starting point. On February 2, 2011, eleven days before the fall of Mubarak, Giza's camel drivers charged on the revolutionary protesters in Tahrir Square. Behind the "Battle of the Camel", Mubarak's clan had promised these desperate camel drivers that trade would resume if they crushed the protesters.

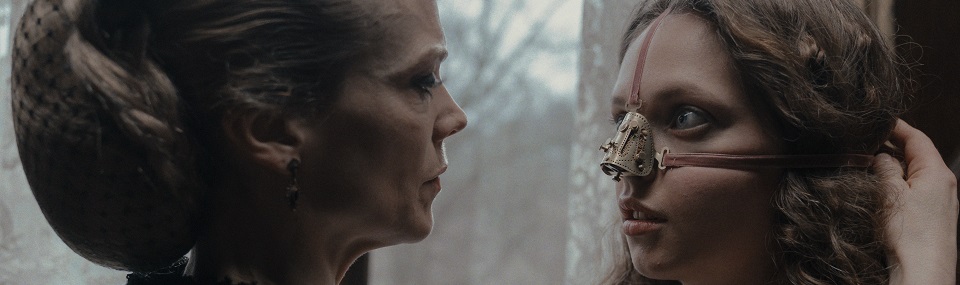

"Thug is a job, and rider is another. They live from tourism and there are no more tourists," explains Reem (Menna Chalaby), a young, wealthy, educated, and emancipated revolutionary. Reem has protested on Tahrir Square and has been the victim of government repression, notably at the hand of its thugs. Yet she develops feelings for Mahmoud (Bassem Samra), a poor rider and father who was among those who charged at the protesters on the day of the battle and who fell, beaten up by protesters. Misunderstood by the revolutionaries who do not grasp manipulation and mocked by his community for his shameful fall at the hands of the protesters, Mahmoud loses his references. He is married. He has children, but between him and Reem, a romance is born that goes beyond their difference in social class. Mahmoud is torn between his desire to go back in time - mostly for economic reasons - and a different future for his children. When one of his sons says that he wants to be a rider when he grows up, his father is thrown into a violent rage: "I would rather see you dead." Because Mahmoud, his dear horse, and the economic system born of tourism to the Pyramids from which his family and neighbours make a living are all doomed to extinction. The walls are closing in on him. He can't even climb the pyramids like he used to when he was a child. His field of vision is now blocked by a wall - a very real wall - that masks the horizon.

After the revolution, Egyptian filmmakers were divided. Should they urgently report what their country had just lived through or, rather, was it better to wait for sufficient distance from the events that had so marked Egyptian culture and politics? Yousry Nasrallah threw himself into shooting, reportedly for up to six months, as political events in Egypt continued to unfold. After the Battle evolved as a consequence of these, and at times you can feel this in the film's uneven pace. The film, edited from 8 hours of rushes, soon developed from a Romeo and Juliet at the foot of the pyramids into a story with very different issues at stake. Even the first four-hour edit continued to change as a result of the constant flux of political events. After the Maspero massacre last October (during which 28 protesters were killed in front of state television headquarters), Nasrallah opted for a fatal, but nevertheless open ending to his film. This climatic ending is no doubt the most beautiful moment of the film, which was screened in Cannes just five days before the Egyptian presidential elections, before the next battle.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.